This essay first appeared in the 12/27/96 issue of East Bay Express. Eighteen years later, on the 5th day of Christmas, it feels as much a seasonal post as anything new I might write.

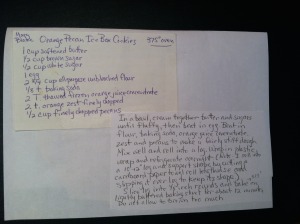

A week before Thanksgiving, and I’m making a list. Canned pumpkin. Evaporated milk. Nutmeg, allspice, and – after double-checking the cupboard – cinnamon: spices I won’t use again until next year. I flip through The Joy of Cooking to a page stained with flour and butter, and after reviewing Basic Pie Crust, lift the sack of flour next to the Special K to feel if there’s enough in it. There is. I multiply all amounts by three, stick the list to the refrigerator, and decide to go to the store one day on my way home from work. I’ll make the crust dough on Tuesday night so it can chill, and do the baking on Wednesday. I’ll find a flat box to carry the pies to Redwood Center, a resident drug rehab program, on Thursday morning before going to my parents’ house for Thanksgiving. That’s the plan.

But the list stays on the refrigerator, where I forget it each morning as I leave for work and avoid it when I get home. Its six ingredients stare at me—“evap milk,” canned pump,” “Crisco,” and the three spices—familiar in my own handwriting but somehow foreign, too, as I feel increasingly uneasy about not following through on my own good intentions. And then, on Monday night, with only one shopping day left, I know why. The image rises in my mind: a group of men, standing in the sunshine on the front steps of Redwood Center, smoking and joshing nervously as they wait for visiting relatives. I see myself drive up, greet them, carry the pies indoors. I see myself leave, lifting my hand to signal good-bye, good luck, and pulling my car up the hill to head north toward the freeway, to drive away alone. My brother won’t be there to fidget, to hug me, to eat my pies. He’s the reason I’ve written down those ingredients and planned this baking session, and he’s the reason—I suddenly realize, as I pull the list from the magnet – that I can’t go through with it.

Four years ago, my brother was a resident at Redwood Center. He’d been in rehab before, but this was the first program he took seriously. I drove down to spend Thanksgiving Day with him, and we talked, for the first time in years, about our nervousness around each other, about our mutual hurt and love, about our childhoods. It was the first time we were able to connect in many years. He was sober, clean of alcohol and cocaine for two months that day, and his racing adrenaline, his nervous jumpiness, had slowed down. What he called his humor mask had slipped, and he was just himself—gentle and sweet and a pleasure to be around. We hiked behind the center and played badminton outside the main build. We sat on a picnic table and talked. We hugged, and cried, and we laughed and cried some more. Relief and joy coursed through me that day. I’ve always enjoyed Thanksgiving, but that year was the best ever, and it had nothing to do with turkey. That year I had my brother back.

My brother had been using drugs – every day, he told me – since he was fourteen. He was then 25. As we climbed the hill behind Redwood Center, ducking beneath low madrone branches and pushing past manzanita, he explained to me one of the lessons his recovery had taught him: that his maturity had been stunted at the age he started using. He was physically 25 and emotionally fourteen. That’s why, he told me, he was lashing out sometimes, impatient other times. “I’m still an adolescent,” he said, with a rueful but not sad smile. “I’m making up for lost time.” He explained how the security of Redwood Center had helped him in this, helped him to feel safe. “Out there,” he said – and we both knew he meant our family living room as well as the streets – “I don’t have that safety, I’d be too tempted to get high as a way of dealing.”

I thought of how a psychotherapist had once told me, “You can’t have a relationship with your brother because your brother is an addict, and an addict loves only thing: his drug.” Her words had seemed so harsh when I first heard them, but now I recognized their truth. I thought of all my short-lived romantic relationships, my unstaunchable sadness and loneliness, and thought how I too had been held back for all those years by loving someone who couldn’t love me back.

My brother died three years ago next month. After Redwood Center, he relapsed onto the streets and into crime and crack, and then found another good program, a program that supported his struggle for sobriety for several months before he slipped again—over the holidays in 1993. His sobriety ended, again, but the connection we reforged that Thanksgiving Day at Redwood Center did not weaken: over long-distance collect phone calls from street corners and jails, over diner breakfasts and sushi dinners, we talked and shouted and swore and cried and laughed. Until the day he died, we were back in each other’s lives again.

I think about the men in Redwood Center this year, catching up with their demons, and would like to feed them something homemade, a sweet tasty pie baked in a crust rolled out by hand. I don’t like backing down on my good intentions. But as I stand in the kitchen holding my crumpled shopping list, I remember those years of silence and anger and confusion and desperation. His, OK—but mine too. I remember watching my brother across a holiday dinner table to see if he would meet my eyes, and I know I’m angry again. Angry at him for dying, for not staying clean, for leaving me. I’m tired of being the good girl, of doing the right thing, of putting out effort for someone who isn’t even alive anymore. There’s a whole piece of loving an addict, a chunk of anger and resentment that buildings from watching the one you love slowly kill himself. This piece doesn’t negate or deny the love, but sits right next to it – a hard, black nugget. It’s rough-edged and painful and not pretty, but claiming that nugget has something to do with being able to move on, a move I have dreaded since that day I first knew I’d have to do it.

There are thousands of addicts in the Bay Area this holiday season, and there are the people who love them. For alcoholic reciting the Serenity Prayer at a crowded AA meeting, there is a mother who is trying to keep the turkey from drying out, worrying that there will not be enough under the tree and that her daughter will show up high to Christmas dinner or husband sneak a drink at the neighborhood open house. For every junkie skulking in a doorway, there is a son who sits quietly through the family meal, stomach in a knot, because he wants to throw a plate against the wall and yell at the sister who is using, the mother who pretends everything is fine. Our pain is quieter than the destructiveness and rage of the addicts and alcoholics we love, and it shapes us into who we are. We don’t crash cars or break into liquor stores or hide cocaine in the underwear drawer. We maintain. We are used to maintaining.

And maybe, just maybe, that maintaining can move into forgiveness. Once again this year, my parents and I sit together and remember the son and brother who made us laugh, whose eyes sparkled with humor and kindness, who woke me every Christmas morning of our childhood so neither of us would be first at the tree, who smiled at me over the passed Brussels sprouts. Once again I look at the picture taken at Redwood Center four years ago, of my brother and me standing next to the madrone and manzanita, and I remember the words with which we found our way back to each other. And, throughout the holidays, I think of how many of us there are, working hard as we trim the tree and light the candles, as we close our eyes and whisper our prayers and wishes, as we roll out pie crust and open greeting cards, as we stand together in our invisible circle of silent, resilient love.